Guest Post: Remembering Srebrenica

I was just ten years old when the Bosnian War started. Growing up in the idyllic surrounds of the Columbia River Gorge in Oregon, I was utterly unable to imagine what exactly was happening on the other side of the world in a war that was barely peaking into my consciousness. I knew it seemed like a big deal that Europe, having been scarred by two world wars, was once again playing host to bloodshed on a massive scale, but I was too young to understand the true significance of the conflict.

In 2009, when I was working at the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia, we produced a play, Scorched, that depicted a country gripped by a genuinely uncivil war. The play is based on Lebanon’s civil war but is set ambiguously. The director, Blanka Zizka, and dramaturg Walter Bilderback wanted to go deeper. And so, we delved into global civil wars and genocides of the Post-WWII era.

That was when I started to understand what had happened during the Bosnian War and at Srebrenica in particular. It was eye-opening.

From our closet office in Philadelphia, I consumed books that outlined the events of the Bosnian War and the even more terrible events leading up to July 11th and its immediate aftermath. So, when I had the opportunity to visit Bosnia, I felt the pull to see in person the place I had learned about through books.

I booked a tour through Funky Tours and was lucky in a couple of respects: it turned out to be a personal tour for just me, and my guide, Adnan, was a veteran of the Bosnian War who had been trained in and served first in the Yugoslav National Army and then, after Bosnia’s independence, had been stationed in Sarajevo for almost the entire conflict. Adnan had worked for an aid organization in Srebrenica throughout the 2000s and was intimately familiar with its history.

As Adnan drove us from Sarajevo through the Republic Srpska to Srebrenica, he told me about the history leading up to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Bosnia’s bid for independence from “greater Serbia,” and the bloody conflict.

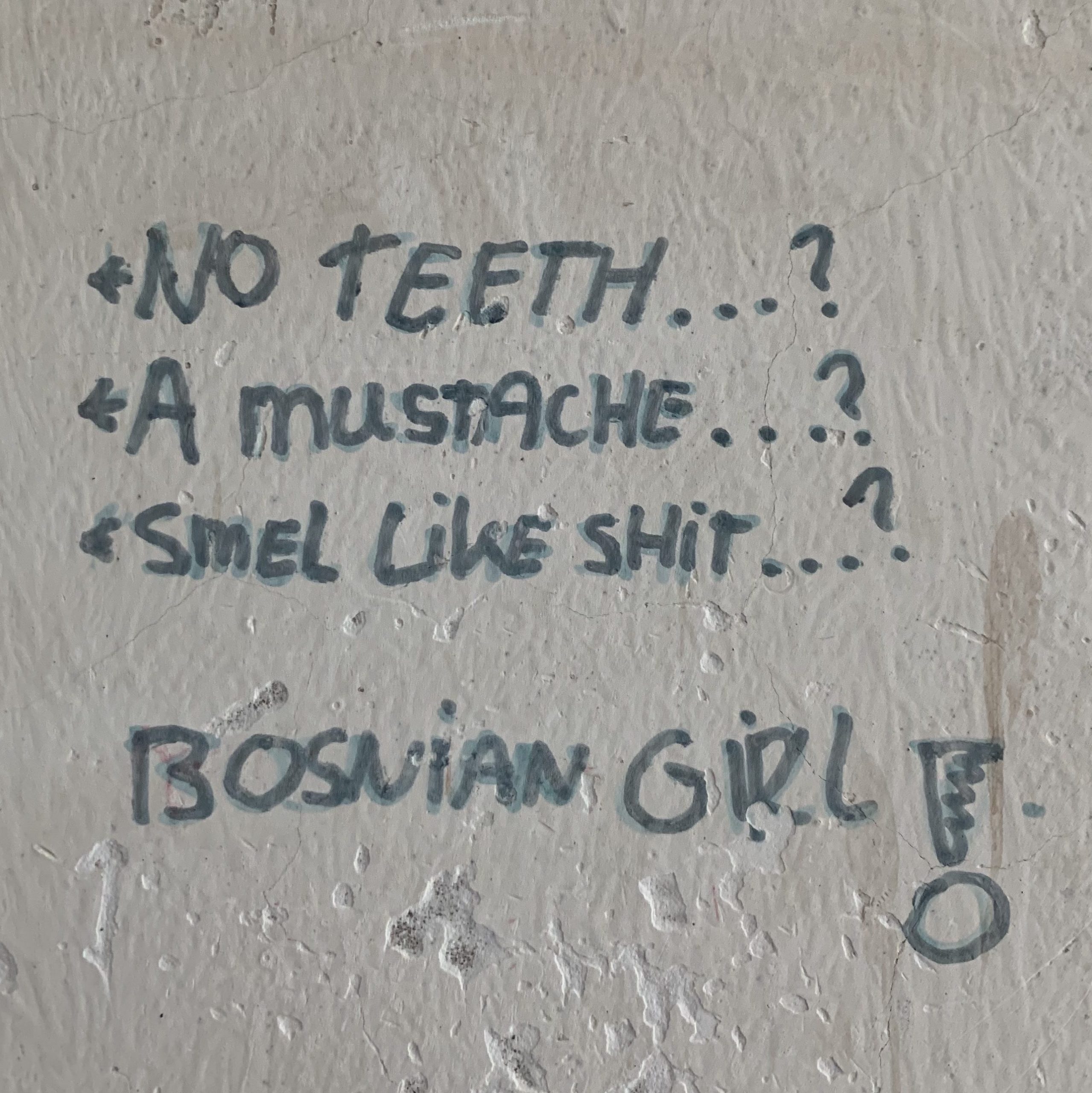

The leading players in the drama were the Bosniak Muslims who constituted a majority in Bosnia and the Bosnian Serbs who sought to gain a Serbian Orthodox state. The Serbs sought to be part of “Greater Serbia” and free of the Muslims, widely seen as interlopers squatting on historically Serbian land. Often referred to as “Turks” for their historical connection to the Ottoman Empire and its heir, modern Turkey, the overtones of racism were hard to miss. Also hard to miss, especially while viewing footage of Orthodox Serbian priests blessing soldiers and weapons for the war effort, were the overtones of a Christian Holy War against infidel Muslims.

Srebrenica, a town consisting of 73% Bosnian Muslims and 25% Bosnian Serbs, held strategic importance as a bridge between Serbia and the Republic Srpska. It was also situated in a region that many Serbs believed historically “belonged” to them. This confluence of racism, holy war, strategy, and historical jingoism would set the stage for the impending genocide.

In 1992, a Serbian paramilitary group briefly took the town, but Bosnian forces retook it shortly after that. Siege conditions prevailed as Serb forces increasingly cut it off from other areas under Bosnian Muslim control. These skirmishes led to intervention by the United Nations. A French general with UNPROFOR, Phillippe Morillon, visited the city. After considerable cajoling and desperate demands from the residents, he pledged that he was with them, that he would protect them, and that he would never abandon them. Strong words, but as history would bear witness, they were not backed by concrete action.

As early as 1992, the Serbs were engaged in campaigns of ethnic cleansing in the area, demanding upon their first capture of Srebrenica that all Muslim inhabitants leave the city. This demand was repeated frequently by Serb forces as they engaged with the local leaders and with UN leaders negotiating on behalf of a peaceful settlement. The Serbs engaged in a starvation tactic to kill as many as possible and encourage the Muslims to surrender. They cared less about weapons finding their way into the enclave and more about food reaching the town’s inhabitants. This tactic continued for the duration of the conflict. Serbs blockaded international convoys meant to bring in assistance for the starving refugees.

With the conflict in the region mounting, the UN declared the area around Srebrenica a Safe Zone—an act that records show suited the Serbs just fine as they believed it would concentrate the Muslims in one place and make them easier to manage. Refugees, harassed by Serb sorties in the area, made their way to the Safe Zone, and soon many tens of thousands surrounded the UN base in Potočari.

After two years of siege, things deteriorated in the summer of 1995. The Serbs, emboldened by a lack of action on the part of the UN, decided to take the entire Safe Zone through military dominance. Starting on July 6, 1995, a Serb force whittled away at the UN positions in the area. The UN forces begged NATO for airstrikes, but these were not forthcoming, and the advance continued.

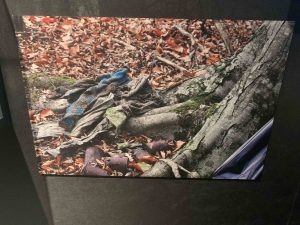

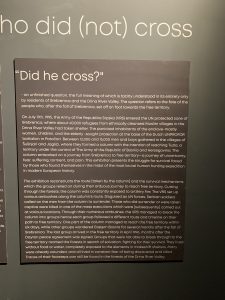

On the ground at the “Dutchbat” in Potočari, the location of the central refugee encampment, terror was beginning to set in as the refugees realized that the UN had little will or ability to stem the Serb onslaught. A large group of men and boys decided that they would make their way through the dense woods in hopes of reaching Bosnian-controlled territory, about a three-day journey by foot from Srebrenica. A group of several thousand set out, but due to heavy shelling by the Serbs and the high number of wounded in the group, the Serbs split the column into two groups. Those in front ended up making it to Bosnian-held territory, while those in the rear did not.

With half their quarry hiding in the woods, the Serbs resorted to asking those they had captured to tell the others hiding up in the forest to come down—imploring them it was safe to do so. The Serbs preserved these moments in videos that documented their activities with perverse home movies. One particularly heartwrenching video shows a Serb officer urging a father to get his son to come down to the Serbs, that it was safe to do so, and that he should encourage others to do the same. Neither of the men survived. The Serb’s video of the incident serves as the final testament to the last few hours of the men’s lives.

Many in the vanguard of the column made it to safety, but most in the second group did not.

Meanwhile, back at the Dutchbat, the Serbs finished their advance. They surrounded the military installation and the refugee camp. The Dutch soldiers had allowed only pregnant women and women with tiny children into the base itself, merely a couple of thousand. The rest were left to fend for themselves. The Serb commander on the ground, General Ratko Mladić, gave a group of representatives from the Muslim refugees a “choice”: “You can either survive or disappear.” These were haunting and cryptic words that confused those hearing them in real-time as much as they mystified me decades later.

Some key takeaways from my visit to Srebrenica

- Another American was visiting the center at the same time as me. She had asked to speak to a representative from the museum. She wanted to explain that her long-time friend from Serbia had claimed that the genocide was faked. The woman was overwhelmed by the museum, the memorial, and all the evidence before her and sought guidance on what to say to her friend. This sentiment appears somewhat common in Serbia to this day.

- Houses up and down the valley were empty, abandoned. It was explained to me by Adnan that these were the remnants of homes whose families had been wiped out in the genocide. They stood as lonely reminders, unintended memorials to the dead.

- Despite the West’s talk of “never again” when it comes to genocide, our track record in this regard is painfully poor. Rwanda. Bosnia. Now, amongst even our own, some people deny these events occurred. Now, we sit and do nothing as genocides occur in Myanmar, China, and other places that haven’t risen to a place in our collective consciousness. It truly feels as though we’ve learned very little.

- The callous reactions of the Dutch soldiers to the refugees, in particular, were painful to realize. The soldiers sent to protect the people of Bosnia casually participated in their dehumanization.